Cracking the Double Precision Gaussian Puzzle

In my previous post, I stated that some library (SPECFUN by W.D. Cody) computes \(e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}\) the following way:

xsq = fint(x * 1.6) / 1.6;

del = (x - xsq) * (x + xsq);

result = exp(-xsq * xsq * 0.5) * exp(-del *0.5);where fint(z) computes the floor of z.

- Why 1.6?

An integer divided by 1.6 will be an exact representation of the corresponding number in double: 1.6 because of 16 (dividing by 1.6 is equivalent to multiplying by 10 and dividing by 16 which is an exact operation). It also allows to have something very close to a rounding function: x=2.6 will make xsq=2.5, x=2.4 will make xsq=1.875, x=2.5 will make xsq=2.5. The maximum difference between x and xsq will be 0.625.

(a-b) * (a+b)decomposition

del is of the order of 2 * x * (x-xsq). When (x-xsq) is very small, del will, most of the cases be small as well: when x is too high (beyond 39), the result will always be 0, because there is no small enough number to represent exp(-0.5 * 39 * 39) in double precision, while (x-xsq) can be as small as machine epsilon (around 2E-16). By splitting x * x into xsq * xsq and del, the exp function works on a more refined value of the remainder del, which in turn should lead to an increase of accuracy.

- Real world effect

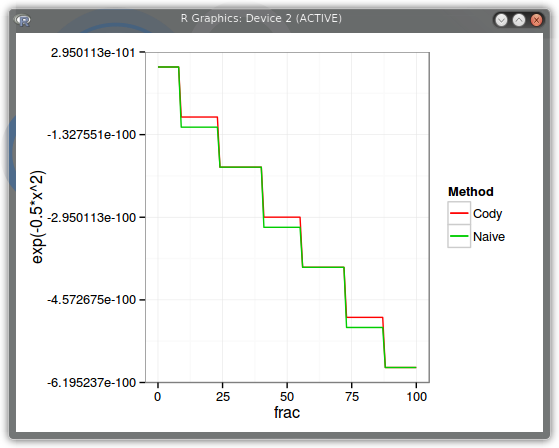

Let’s make x move by machine epsilon and see how the result varies using the naive implementation exp(-0.5*x*x) and using the refined Cody way. We take x=20, and add machine epsilon a number of times (frac).

PDF

To calculate the actual error, we must rely on higher precision arithmetic. Update March 22, 2013 I thus looked for a higher precision exp implementation, that can go beyond double precision. I initially found an online calculator (not so great to do tests on), and after more search, I found one very simple way: mpmath python library. I did some initial tests with the calculator and thought Cody was in reality not much better than the Naive implementation. The problem is that my tests were wrong, because the online calculator expects an input in terms of human digits, and I did not always use the correct amount of digits. For example a double of -37.7 is actually -37.

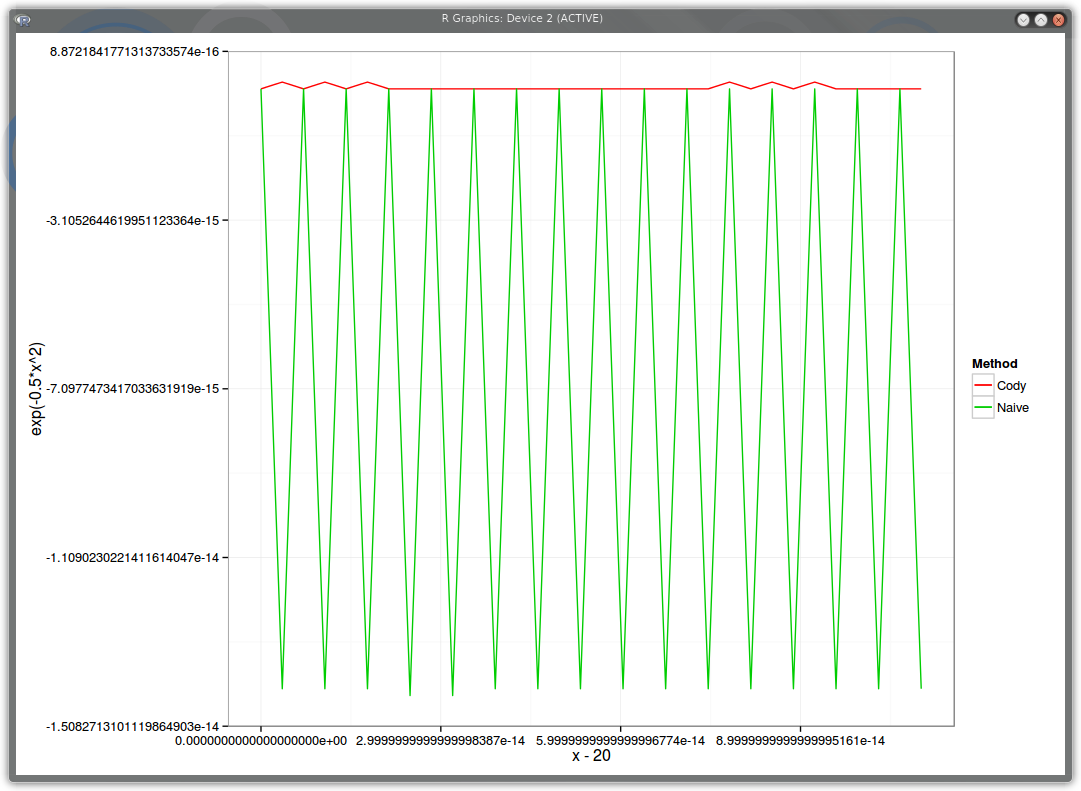

Here is a plot of the relative error of our methods compared to the high accuracy python implementation, but using as input strict double numbers around x=20. The horizontal axis is x-20, the vertical is the relative error.

PDF relative error around x=20

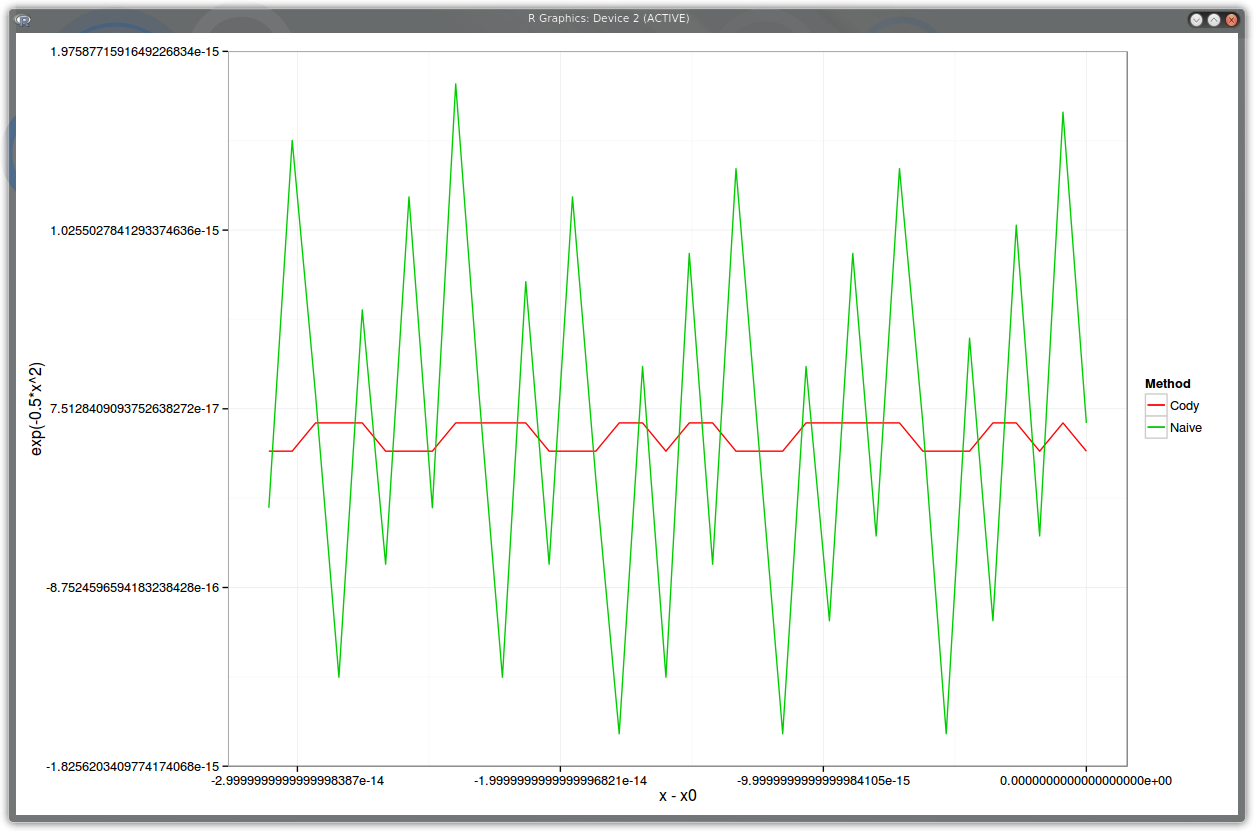

PDF relative error around x=-5.7

Any calculation using a Cody like Gaussian density implementation, will likely not be as careful as this, so one can doubt of the usefulness in practice of such accuracy tricks. The Cody implementation uses 2 exponentials, which can be costly to evaluate, however Gary Kennedy commented out that we can cache the exp xsq because of fint and therefore have accuracy and speed.